Typography hierarchy isn’t just about making things look pretty—it’s about survival in information overload.

I used to think that font sizes and weights were basically designer vanity, you know, the kind of thing people obsess over in mood boards but doesn’t actually matter in the real world. Then I spent three hours trying to navigate a government healthcare portal where every single line of text was the same size, same weight, same everything. By minute forty-five, I wanted to throw my laptop out the window. That’s when it hit me: hierarchy isn’t decoration, it’s cognitive scaffolding. Our brains are pattern-recognition machines that evolved to scan savannas for threats and food sources, not to parse dense blocks of identical text on glowing rectangles. When everything screams at the same volume, nothing gets through. We need visual variation—big versus small, bold versus light, spaced versus tight—to create a mental map of what matters and what’s just context. Without that map, we’re essentially reading with one hand tied behind our backs, forcing our working memory to do all the heavy lifting that good typography should handle automatically.

The Three-Second Rule and Why Your Eye Knows Where to Land Before Your Brain Does

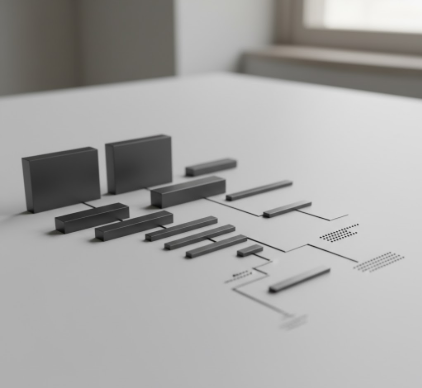

Here’s the thing: effective hierarchy works in roughly three seconds or less. That’s the window where users decide if they’re staying or bouncing. Eye-tracking studies show that people don’t read websites or documents linearly—they scan in F-patterns or Z-patterns, hunting for entry points. Large headings act as anchor points, subheadings create rhythm, and body text fills in the details once you’ve decided to commit. The size differential matters more than you’d think, actually—most designers recommend at least a 2:1 ratio between heading and body text, sometimes more.

I guess it makes sense when you consider that newspapers figured this out over a century ago. Turn back the clock to the 1890s, and you’ll find front pages with headlines screaming in 72-point type while the article text huddled below in something like 9-point. They understood attention economics before we had a term for it. Digital design just rediscovered the wheel, honestly, though we did add some new tricks—like using weight and color alongside size to create multiple levels of emphasis without making everything gigantically oversized.

Wait—maybe the most interesting part is how hierarchy handles complexity without simplifying it.

Think about a subway map or an airport signage system. These are wildly complex information architectures serving millions of people who speak different languages, have different literacy levels, and are often stressed or rushed. The typographic hierarchy does insane amounts of work here: destination names are huge and bold, platform numbers are medium and distinct, fine-print warnings are small but still legible. Each level has a job. Remove that structure, and you’ve got chaos—I’ve seen this happen in real time when cities launch “modern” redesigns that flatten everything in the name of minimalism, and suddenly nobody can find the damn exit. The hierarchy isn’t just organizing information, it’s triaging attention in real-time, telling your visual system what to grab first, second, third. It’s essentially a priority queue rendered in fonts and spacing, which sounds cold and technical but actually feels totally intuitive when it’s done right, almost invisible.

Contrast, Consistency, and the Cognitive Load Problem Nobody Talks About Enough

Contrast is where hierarchy gets its power, but consistency is what makes it learnable. If your H1 is 36pt Helvetica Bold on page one and 28pt Georgia Regular on page two, you’ve just made your user recalibrate their entire mental model. That recalibration costs cognitive load—the mental effort required to process information—and humans have a pretty limited budget for that stuff. Studies suggest we can hold maybe seven chunks of information in working memory at once, give or take. Good hierarchy reduces the chunking work by making patterns predictable: big thing equals important, small thing equals detail, bold thing equals action. Once users internalize that pattern, they stop thinking about it consciously, which frees up brain power for actually understanding the content instead of decoding the interface.

Honestly, I think we underestimate how exhausting bad typography is.

A few years back, I read a study—can’t remember the exact journal, maybe it was in Applied Cognitive Psychology or something adjacent—that measured reading speed and comprehension across different typographic treatments. Turns out people reading well-hierarchized documents not only processed information faster but also retained more and reported feeling less fatigued afterward. The effect wasn’t huge, maybe 15-20% improvement, but that compounds over time. Spend eight hours a day reading poorly designed documents, and by Friday you’re definately going to feel it. The typography isn’t just organizing information—it’s managing your energy expenditure, doling out cognitive resources strategically so you don’t burn out before you get to the important bits. Which is wild when you think about it, because most people never consciously notice the font sizes or spacing ratios, they just know something feels easy or hard to read, and that feeling shapes whether they engage or disengage entirely.