Neo-Dada didn’t ask for permission.

When Robert Rauschenberg erased a Willem de Kooning drawing in 1953, he wasn’t just making a statement about authorship or the commodification of art—he was continuing a conversation that Marcel Duchamp started decades earlier with his urinal-as-fountain. But here’s the thing: Neo-Dada wasn’t a simple revival. It was more like a cover band that accidentally wrote better songs than the original. The artists of the 1950s and 60s—Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Yoko Ono, and others—took Dada’s nihilistic rejection of bourgeois art and twisted it into something stranger, more commercial, and definately more American. They used found objects, performance, and mass-produced imagery to blur the line between high culture and garbage, and in doing so, they created a template for how contemporary artists still operate today.

The Uncomfortable Resurrection of Duchamp’s Readymades in Postwar America

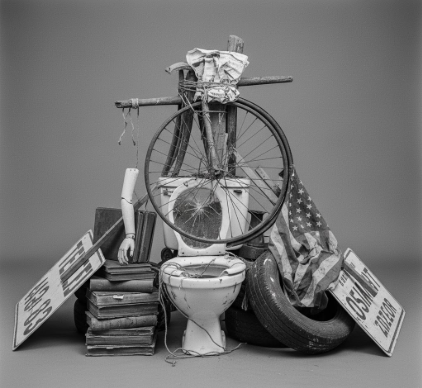

I used to think Duchamp’s readymades were about shock value. Turns out, they were about questions no one wanted to answer. When Johns painted his first American flag in 1954, critics didn’t know if it was a painting of a flag or just a flag. That ambiguity—wait—maybe that’s the whole point? Neo-Dada artists weren’t interested in destroying art institutions the way the original Dadaists were; they were interested in infiltrating them. Rauschenberg’s “Combines” mixed painting with sculpture, photography, and literal trash. One piece included a stuffed angora goat with a tire around its middle. Museums didn’t know whether to hang it or call animal control.

The original Dada movement emerged from the trauma of World War I, roughly around 1916, give or take. It was angry, European, and deeply suspicious of anything that smelled like nationalism or rationality. Neo-Dada, by contrast, emerged in a postwar America that was booming, consumerist, and oddly optimistic despite the Cold War. So the anti-art attitude shifted: instead of rejecting art entirely, Neo-Dada artists asked why we valued certain objects and not others.

How Fluxus and Happenings Turned Galleries Into Participatory Chaos Events

Honestly, the Fluxus movement was a mess—and that was intentional.

George Maciunas, who sort of organized Fluxus (though “organized” is generous), wanted art to be cheap, expendable, and available to everyone. Fluxus events were part concert, part prank, part existential crisis. Yoko Ono’s “Cut Piece” from 1964 invited audience members to cut away her clothing with scissors while she sat motionless on stage. It was uncomfortable. It was supposed to be. Allan Kaprow’s “Happenings” turned viewers into performers, erasing the boundary between artist and audience. These weren’t performances you could recieve passively—you were implicated, whether you liked it or not. The anti-art attitude here wasn’t about rejecting beauty or skill; it was about rejecting the idea that art should be a commodity you hang on a wall and ignore.

Why Contemporary Artists Still Use Trash and Provocation as Visual Language

I’ve seen a lot of contemporary art that feels like it’s trying too hard to be Neo-Dada. A banana duct-taped to a wall (Maurizio Cattelan, 2019) sold for $120,000. Is that genius or a joke? Maybe both. The point is, the anti-art attitude didn’t die—it just got absorbed into the market it was supposed to critique. Artists like Ai Weiwei, Banksy, and Kara Walker use provocation, found materials, and institutional critique in ways that echo Neo-Dada’s playbook. Walker’s silhouettes force viewers to confront racism and violence; Banksy’s street art mocks the gallery system even as his work sells for millions.

The irony is thick enough to choke on. Neo-Dada wanted to democratize art, but now its influence is everywhere from Instagram aesthetics to NFTs. The anti-art gesture has become a brand.

The Paradox of Anti-Art Becoming the Most Expensive Art in Auction Houses

Anyway, here’s where it gets weird.

In 2017, Leonardo da Vinci’s “Salvator Mundi” sold for $450 million. That same year, a Rauschenberg “Combine” sold for $88.8 million. The difference? One is a Renaissance masterpiece (sort of—some experts dispute its authenticity). The other is a painting with a pillow and a quilt attached. Both are expensive. Both are considered “important.” Neo-Dada’s anti-art attitude was supposed to challenge the idea that art’s value comes from rarity, technique, or institutional approval. Instead, it just created a new category of expensive objects. Museums and collectors love Neo-Dada now because it has historical weight. It’s safe. It’s canonical.

I guess it makes sense. Rebellion, once documented and archived, becomes history. And history sells.

The contemporary visual culture we inhabit—where memes are art, where performance is content, where provocation is currency—owes a massive debt to Neo-Dada. But it’s a complicated inheritance. The anti-art attitude survives, but it’s been bent, stretched, and repackaged so many times that it’s hard to tell what’s genuine critique and what’s just marketing. Maybe that’s the final joke: Neo-Dada succeeded so well at infiltrating the art world that it became indistinguishable from it.