I used to think design was supposed to be universal—like gravity, or something.

The modernists certainly believed it. Bauhaus, the Swiss Style, International Typographic Style—they all preached this gospel of clarity, grids, sans-serif fonts that could speak to anyone, anywhere. The idea was that if you stripped away cultural ornament, you’d reach some kind of pure visual language that transcended borders. Helvetica was supposed to be neutral. White space was supposed to be rational. Form followed function, and function was supposedly the same whether you were in Zurich or Tokyo. It was a beautiful dream, honestly, and it produced some iconic work. But here’s the thing: it was also kind of a lie, or at least a very particular Western European fantasy dressed up as objective truth.

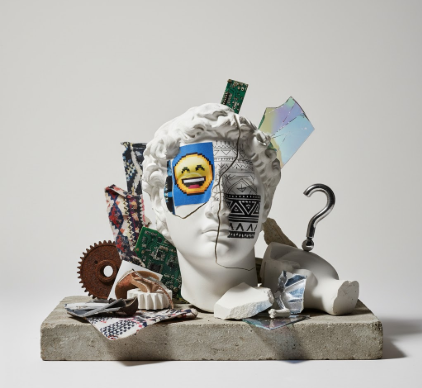

Postmodernism arrived in the 1960s and 70s like a wrecking ball made of irony and pastiche. Designers like April Greiman, Wolfgang Weingart, and the Memphis Group started layering references, mixing historical styles, embracing chaos and decoration. They weren’t just rebelling for the sake of it—they were pointing out that “universal” design was never really universal at all.

The Cracks in the Modernist Grid Started Showing When Culture Wouldn’t Stay Out

Wait—maybe the clearest example is typography. Modernists loved their grids and their rationalized letterforms, but postmodernists started asking: rational according to whom? The Latin alphabet? Western reading patterns? What about cultures with vertical text, or right-to-left scripts, or visual traditions that valued asymmetry and complexity over reductive clarity? Turns out, the “international” style was really just international among a pretty narrow slice of the globe. I guess it makes sense when you realize most of its pioneers were European men working in the mid-20th century, but it’s still jarring to see how confidently they declared their aesthetics universal.

Postmodern designers didn’t just critique—they built alternatives. They pulled from vernacular sources, embraced kitsch, layered meanings until clarity became secondary to richness. Neville Brody’s work for The Face magazine in the 1980s, for instance, treated the page as a playground where legibility was negotiable and cultural references piled up like a collage. It was messy. It was definately not neutral.

And it was honest about what design actually is: a cultural product, shaped by the designer’s context, speaking to specific audiences in specific moments.

The backlash was immediate, of course. Massimo Vignelli—one of modernism’s great defenders—famously said the postmodern designers were “polluting” design with their lack of discipline. But that’s exactly the point postmodernists were making: who gets to decide what’s pollution and what’s culture? Who gets to say that a Didot serif is sophisticated but a decorative Arabic calligraphic tradition is too “ornamental”? The power dynamics were always there, hiding behind the language of universality. Postmodernism just made them visible, sometimes with a smirk, sometimes with genuine anger. I’ve seen design historians argue that postmodernism’s real contribution wasn’t any particular style—it was permission. Permission to acknowledge that design is rhetorical, that it carries ideology, that “neutral” is just another aesthetic choice with its own baggage.

Pluralism Replaced the Fantasy of a Single Visual Esperanto

By the 1990s, the conversation had shifted. Designers weren’t asking “what’s the one true way?” anymore. They were asking “whose way, and for whom?” Digital tools accelerated this—suddenly you could mix fonts, warp grids, recieve instant feedback from global audiences who’d tell you real quick if your “universal” design didn’t speak to them at all. The web especially democratized design production, and with it came an explosion of aesthetic diversity that would’ve horrified the Bauhaus faculty.

Anyway, the legacy is complicated.

Postmodernism opened doors, but it also sometimes reveled in obscurity for its own sake, alienating audiences in different ways than modernism did. And plenty of contemporary design still leans on modernist principles—minimalism never really went away, it just got an iPhone and called itself flat design. But the assumption that design can or should be universal? That’s mostly dead. We talk about inclusive design now, accessible design, culturally responsive design. We acknowledge that different communities have different needs, different visual literacies, different histories that shape how they read images and text. It’s messier than the modernist dream, sure, but it’s also more honest about the world we actually live in—one where meaning is multiple, context is everything, and the grid was never as neutral as we pretended it was.