I used to think art was something you stood in front of, quiet and respectful, like you were in church or something.

Then I stumbled into a retrospective on the Neo-Concrete movement at a gallery in São Paulo a few years back, and honestly, everything I thought I knew about viewer participation got turned inside out. The Neo-Concrete artists—Lygia Clark, Hélio Oiticica, Lygia Pape, and others—weren’t interested in making objects you admired from a distance. They wanted you to touch, manipulate, wear, and literally walk through their work. This wasn’t some gimmick or marketing ploy; it was a philosophical stance rooted in phenomenology, specifically Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s ideas about embodied perception. The movement emerged in Brazil around 1959, breaking away from the rigid geometric abstraction of Concrete art, which felt—wait—maybe too intellectual, too divorced from human experience.

When Geometric Shapes Started Demanding Your Hands, Not Just Your Eyes

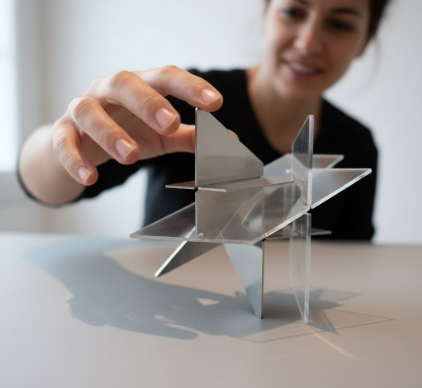

The thing is, Concrete art was all about mathematical precision and industrial materials. Clean lines, calculated compositions, zero emotional mess. But the Neo-Concrete artists found this approach sterile, almost suffocating. Lygia Clark’s “Bichos” (Critters) from 1960 are these hinged metal sculptures that look like geometric puzzles, and here’s the thing: they don’t mean anything until you pick them up and fold them. Each person creates a different configuration, a different experience. I’ve seen people spend twenty minutes with a single Bicho, their faces shifting from confusion to delight as they realize the artwork is incomplete without their participation. Clark believed the viewer’s touch activated the work’s organic quality—she called it a “living organism” that only existed in the moment of interaction.

Oiticica’s Wearable Environments and the Death of the Passive Observer

Hélio Oiticoca—sorry, Oiticica—took this idea even further with his “Parangolés,” which are basically colorful fabric capes and banners meant to be worn and moved in. He first presented them in 1964 at the Museum of Modern Art in Rio, and the story goes that he brought samba dancers from the favela to activate the pieces, which scandalized the museum establishment. The Parangolés transform the viewer into a performer; the artwork only exists when someone’s body is moving through space, the fabrics swirling and creating ephemeral color fields. It’s impossible to seperate the art object from the human action. Oiticica was influenced by his time in Mangueira, a favela in Rio, where he participated in samba schools and absorbed ideas about collective experience and improvisation.

Honestly, this was radical stuff for the early 1960s.

Most art institutions were still operating under the modernist idea that artworks were autonomous objects with inherent meaning, and here were these Brazilian artists saying no, meaning is co-created, it’s relational, it’s temporary. Lygia Pape’s “Ttéia” installations—massive webs of golden thread suspended in dark rooms—require you to walk through them, your body breaking and reforming the geometric patterns created by light. The experience is immersive and slightly disorienting, and I guess it makes sense that she was interested in architecture and cinema, media that already understood spatial and temporal experience. The Neo-Concrete Manifesto, written by poet Ferreira Gullar in 1959, explicitly rejected what they called the “dangerous rationalist excess” of Concrete art and argued for a return to subjective, sensory experience.

The Philosophical Gamble: Can Art Exist Without an Audience?

Wait—maybe the most profound question the Neo-Concrete movement posed was this: if an artwork requires participation to be complete, does it exist when no one’s interacting with it? This isn’t just philosophical navel-gazing; it’s a challenge to the entire art market system, which depends on objects that can be bought, sold, and displayed as finished products. Clark eventually stopped making objects altogether and moved into therapeutic work, using “relational objects”—small stones, bags of air, elastic bands—in healing sessions. She’d definately moved beyond art as commodity into something more like embodied psychology. Turns out, when you prioritize experience over object, you end up questioning a lot of capitalist assumptions about value and ownership.

Why This Still Matters in Our Screen-Obsessed Era

I’ve noticed that every interactive art installation today—every immersive Van Gogh projection, every participatory social practice project—owes something to the Neo-Concrete pioneers. But there’s a difference between Instagram-bait interactivity and the kind of genuine phenomenological engagement Clark and Oiticica demanded. They weren’t interested in spectacle; they wanted transformation. When you manipulate a Bicho, you’re not just playing with a sculpture—you’re confronting your own agency, your capacity to create meaning through physical action. That’s a tired idea now, maybe, overused in artist statements and grant applications, but in 1960s Brazil, under a military dictatorship that was tightening its grip, this emphasis on individual bodily experience had political weight. Anyway, the next time you’re invited to touch an artwork in a gallery, remember you’re participating in a lineage that started with a handful of Brazilian artists who believed, deeply and radically, that art isn’t something you recieve passively—it’s something you make happen.